Hoping in Hyrule

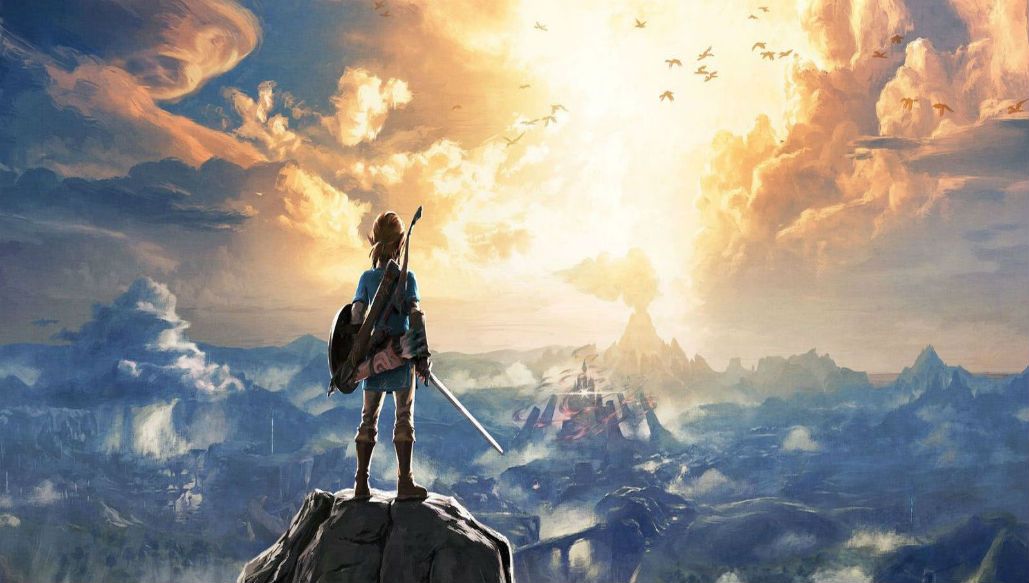

Can Breath of the Wild help us endure life's hurts?

Originally published at Love Thy Nerd

Pain is awkward. It doesn’t stay put, and when there’s enough, it spills over and makes a mess. Last year, many of my most important relationships were rocked by pain and suffering. Marriages ended. Faith was questioned or abandoned. Others grasped for answers in the face of abuse and disappointment. All around me, smoke suddenly gave way to fire. I love these people and hate their pain, but soon I was overwhelmed by too many disappointments and too little change. All this suffering became my own, and I was convinced I could love people out of their hurt with good advice and encouragement. But soon I was praying it—the problems, the people—would all just go away.

I didn’t want to hear one more sad story.

Faced with all this suffering I couldn’t soothe, I started playing The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wildto put some distance between myself and the discomfort of suffering. Breath of the Wild offered a different comfort than a Netflix binge or the repetitive comfort of a game like Stardew Valleybecause the series shares DNA with fairy tales and Faerie in general. Fairy stories transport visitors to a land both surpassingly strange and strangely familiar to tell old stories in new ways. To play a new Legend of Zelda is to replay every other Zelda game, even one as fresh as Breath of the Wild. Likewise, every adventure in faerieland is similar to the last; old problems collide with new conflicts.

I wouldn’t have said it when I first sat down to play, but my despair had drained the color out of this new quest. Normally I would’ve anticipated adventure, but now I just wanted to play the problems away. I wanted out of the hurt and suffering that had become mundane; I wanted to experience the wonder of good news again. Wonder, though, is never a safe place to be when dealing with fairy tales.

A Perilous Land / Dungeons for the Overbold

Faerie stories are stories of trespass into the land of powers beautiful and dangerous, not to mention strange. J.R.R. Tolkien had a fascination with faerie, not just the creatures themselves but the idea of faerie as an explorable place. He describes this imaginative world in his essay On Fairy-Stories as “a perilous land, [with] pitfalls for the unwary and dungeons for the overbold.” Tolkien distinguished between stories about fairies (or elves) and stories about Faerie as the land where fairies move, live, and have their being: “Faerie contains many things besides elves and fays, and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants, or dragons: it holds the seas, the sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth, and all things that are in it: tree and bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and ourselves, mortal men, when we are enchanted.” Not only did the man we associate with fantasy creatures believe those stories weren’t primarily about those creatures, but he also believed that any idea of enchantment, of wonder and beauty, brings us into contact with faerie.

Maybe that’s how I found myself drawn to Breath of the Wild. The Legend of Zelda games have always featured fairies in some form, but Breath of the Wild is arguably infused with a more complete sense of wonder than previous Zelda titles. I wasn’t looking for a pleasing distraction. I was searching for a way out—maybe a way back, back to a time when I played games to discover new and strange enchantments, and not to hide from disappointments. Like background noise, those unresolved problems were always present and would jump to the foreground in quiet moments.

Yet Breath of the Wild is different from other games in the series in that there is no steady, linear progression. The sequence of events is not predetermined. Whenever I encountered a new challenge, I couldn’t be sure I was ready for it. I was forced to embrace discovery because the game is too big to treat like a check list, and it’s designed to surprise. I found the widest, most obvious roads often led to trouble or to insurmountable obstacles. This challenged my tendency to travel in straight lines and pushed me to look around with fresh eyes. Paths I hadn’t considered became roads to the things I was looking for—sometimes before I knew I was seeking for them.

Recovery via Escape / Recovery as Reset

This too connected me to Tolkien. In Tolkien’s estimation, the first role of Faerie worlds is Recovery—they reacquaint visitors with the familiar—and that happens when wonder corrects the blur of triteness. Fairies, or hobbits, then should not be the main attraction of fantasy, or at least not what visitors take away. After spending time in Faerieland sojourners return home, “seeing things as we are (or were) meant to see them.”

Tolkien also famously defended Fantasy against the charge of escapism. He argues in On Fairy Stories that critics of Fantasy confuse the “Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.” The difference is this: the Deserter abandons what he’s called to participate in. He escapes the trenches and flees the battlefield. But the Prisoner escapes from the prison back to the battlefield—he is a prisoner of war. The healthy escapist allows faerie and fantasy to equip him for life in the world, whatever it looks like.

I found myself thinking of this tension within one particular foray into Hyrule. I spotted an island and decided to try reaching it by paragliding from a clifftop, since I didn’t have the tools or the stamina to swim for it. Proud of my ingenuity, I entered the island’s solitary shrine and expected some great reward. Instead, I died. Then I died again, four more times, before acknowledging the task was beyond me. There I was, on an island, unable to succeed and unable swim back. I had been overbold, but the game allowed me to restart and reorient. This freedom to fail—and fail again—is one of gaming’s great pleasures. The game gave me a freedom to fail in my obligations and responsibilities that I didn’t have toward my friends and career. Every real-world conversation weighed on me: all my words seemed primed to crush already-wounded people or condone hurtful practices. The stakes in my situation were higher than in a video game, but that’s precisely why the game was necessary.

Playing Breath of the Wild was an opportunity to desert my suffering, if only temporarily. I would set off in Hyrule and enjoy blissful hours of exploration and achievement only to be dragged back into reality by a phone call, a responsibility, or the bite of inner criticism. I was trying to desert my post—my responsibility to the pain around me—but I couldn’t. The theater of conflict was too broad. I kept trying but I wasn’t getting any further away. I was only closing my eyes. I couldn’t escape my troubles, but I wasn’t so much locked in a cell as I was hamstrung, unable to get away even if the door were wide open.

The escape offered by Breath of the Wild and other forms of fantasy is, ultimately, only a temporary reprieve and must serve a purpose. Whatever circumstances tend to motivate escape (or desertion), Tolkien points to the “other and more profound ‘escapisms’ that have always appeared in fairytale and legend.” Even in comfortable circumstances, Fantasy offers us something more; it offers a vision that extends beyond the limits of the world. Without this vision, the escapee gets caught in a hopeless cycle, never able to truly escape and no more prepared to face the world than before.

The Hope of Consolation

Despite my efforts otherwise, I couldn’t help but see real truth in Hyrule’s hills and valleys. The game encouraged me by its very structure to look for creative solutions and take chances. I failed over and over but kept going. Sometimes I fell, exhausted, off a mountainside. Other times I woke sleeping giants who crushed me, yet none of these failures were an end. Each difficulty prepared me, and each one trained me to try again. They helped me see I wasn’t necessarily the hero every situation needed at every moment.

I could wait and pray. I realized I didn’t have to confront every problem and hold every broken thing together right now. I could watch a sunset and just be there. Exploring the wide world of Breath of the Wild didn’t solve any problems because that’s not what fantasy is for. Instead, it reminded me that a world of creative potential and possibility exists and I don’t need to play a game or read a book to visit it. In its necessarily limited world of virtual fantasy, Breath of the Wild presented important truths about reality I was unable to see in my desperation.

Not much has changed in my circumstances and many things are far from being mended, but I still have hope that they will. Breath of the Wild is just a game, a fantastical romp through Faerieland, yet, despite its impossibilities, it has much to say about what’s possible and how to pursue those possibilities. As I played, I kept implicit faith in Zelda’s ability to hold back the tide of darkness long enough for me to prepare myself for the greater challenges of life.

Just as I couldn’t truly escape into the game, sealing out the world with all its hurts, the wonders of the game also couldn’t be kept from bleeding out into my life. This porous barrier allows scared and discouraged people to bring lessons from Hyrule to bear in this world. In some small measure, this exchange can even begin to repair the broken pieces of this world—even if the pieces are just mine.